KAS Current Affairs

Preliminary Examination

Paper-I: Current Events of National and International Importance

Rajendra Vishwanath Arlekar assumes charge as T.N. Governor

Context: Kerala Governor Rajendra Vishwanath Arlekar, who was appointed by President Droupadi Murmu on March 5 to discharge the functions of the Governor of Tamil Nadu, assumed his gubernatorial office at Lok Bhavan in Chennai.

- Chief Justice of the Madras High Court Sushrut Arvind Dharmadhikari administered the oath of office to Mr. Arlekar.

- The outgoing Governor R.N. Ravi, who served as the Governor of Tamil Nadu for nearly 54 months since September 2021, has been posted as the Governor of West Bengal.

Paper-II: Current Events of State Importance and Important Government Schemes and Programs

Cabinet clears Eva Nammava Eva Nammava Bill

Context: The State Cabinet on Thursday cleared The Karnataka Freedom of Choice in Marriage and Prevention and Prohibition of Crimes in the name of Honour and Tradition (Eva Nammava Eva Nammava) Bill, 2026.

- The decision came at a Cabinet meeting , and is likely to be placed in the ongoing Budget session of the legislature.

- The Bill had come with certain modifications from the previous one. The Cabinet also cleared the Advertisement Policy, 2026. The State Cabinet also cleared the decks for a new international stadium to be built at Surya Nagar 4th Phase in Anekal taluk.

State expands tie-up with British Council to boost Arivu Kendras

Context: Karnataka’s Rural Development and Panchayat Raj (RDPR) Department has expanded its partnership with the British Council to strengthen English language learning, library services, and knowledge access in rural areas through the State’s Gram Panchayat Arivu Kendras (Knowledge Centres).

- Under this expanded collaboration, the number of British Council Library Corners in Gram Panchayat Arivu Kendras will be increased from 10 to 70, with 60 additional centers being established across the state. As part of the initiative, the British Council will provide 3,000 children’s English books and extend free access to its digital library resources, enabling rural readers to connect with global knowledge platforms and curated English learning content.

- “Gram panchayat libraries have evolved into vibrant Arivu Kendras. During the pandemic, these libraries became critical learning spaces for children, and by offering free membership to those in the age group of 6 to 18, we have brought over 5 million young readers into this ecosystem,”.

- “For many young people in rural Karnataka, English language skills are an important pathway to higher education, employability, and social mobility. Our partnership with the British Council helps bring high-quality English learning resources, books, and digital content closer to these learners,”.

Key Features and Overview of Arivu Kendras:

| Feature | Description |

| Origin & Establishment | Rebranded from traditional Gram Panchayat libraries (under RDPR Department) since 2019. |

| Core Philosophy | Democratizing knowledge; shifting from mere “book storage” to “community knowledge hubs.” |

| Digital Infrastructure | Equipped with high-speed internet, computers, tablets, and digital content databases. |

| Target Audience | Rural students, competitive exam aspirants, farmers, and digital-literacy learners. |

| Educational Services | Access to career guidance, competitive exam study materials, and English language training. |

| Special Initiatives | Implementation of assistive technologies (like ‘Tarangini’/’Darshini’ for PwDs) and science outreach programs. |

| Total Coverage | Currently 5,884 active centres (as of March 2026), with a target network of over 12,000. |

| Operational Role | Act as facilitators for government scheme information and digital form-filling. |

Main Examination

Paper-I: Essays

Essay – 1: Topic of International/National Importance

“Cauvery Water Dispute: Implementation of Tribunal Awards, Mekedatu Project, and Challenges in Inter-State Sharing.”

Essay-2: Topic of State importance/Local Importance

“Bengaluru’s Traffic Labyrinth: Problems, Challenges, and Sustainable Solutions.”

Paper-II: General Studies 1

Paper-III: General Studies 2

India co-sponsors UN resolution condemning Iran

Context: India has co-sponsored a resolution at the United Nations Security Council that condemned actions by Iran aimed at interfering with navigation through the Strait of Hormuz.

- The resolution demands the ‘immediate cessation of all attacks by the Islamic Republic of Iran’ on GCC countries; India prioritises the safety of ‘all civilians’, says Ministry in wake of criticism over unbalanced responses on conflict in West Asia.

- India has prioritised the safety of “all civilians”, the government in an effort to deflect criticism that it had only condemned Iran’s actions, and not those by the U.S. and Israel in the ongoing war in West Asia.

- India co-sponsored a Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) resolution at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) along with 134 countries that demanded the “immediate cessation of all attacks by the Islamic Republic of Iran” against GCC countries Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Jordan. The resolution was passed with 13 UNSC members voting in favour while Russia and China abstained.

- It condemned “any actions or threats by the Islamic Republic of Iran aimed at closing, obstructing, or otherwise interfering with international navigation through the Strait of Hormuz”.

- “The resolution reflects several of our positions,” said Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal at a weekly press briefing on Thursday.

- “We have a large diaspora in the GCC countries, and their well-being and welfare are of utmost importance. The Gulf is also very important for our energy security needs,” Mr. Jaiswal added, in references to about 10 million Indians who live and work in West Asia, and India’s energy purchases from the region that make up about 50% of its crude oil and 90% of its liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) imports.

- In contrast, there are about 9,000 Indians in Iran and India has discontinued its energy imports from Iran since 2019, under threat of U.S. sanctions. The Indian support for the UNSC resolution comes on the heels of a number of statements by the Ministry condemning specific Iranian actions such as the attacks on various countries across the West Asian region, buildings in Dubai, Omani facilities and a Thai ship bound for India.

U.S.-Israeli actions

- However, India has not similarly condemned the attacks by the U.S. and Israel on Iran, in which an estimated 1,255 people have been killed, including Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, his family and advisors; the sinking of Iranian ship IRIS Dena in the Indian Ocean that had been hosted for exercises by India; or the bombing of a school in Mubin in which 150 schoolgirls are believed to have been killed. Nor has India or the GCC-led resolution spoken about Israel’s strikes on Lebanon, where the government said more than 630 people have been killed, and 8,00,000 displaced from their homes.

- Mr. Jaiswal said that the MEA had issued statements, and External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar had made suo motu statements in both Houses of Parliament that regretted the loss of lives.

- “As far as the question of the schoolchildren is concerned… we have issued several statements on the ongoing conflict. We have underlined the need for prioritising the safety of all civilians. We regret the precious lives lost, and express our grief in that regard,” Mr. Jaiswal said.

- In the past few days, India’s “silence” on U.S. and Israeli actions has come in for criticism from a number of senior former diplomats speaking to the media and at various public events.

- “Diplomacy should recognise complexity, not reduce it to a single culprit,” former Indian Foreign Secretary and former Ambassador to the U.S. Nirupama Menon Rao said on Thursday in a post referring to the Ministry of External Affairs statement, suggesting that India’s sponsorship of the UN resolution would “endorse a narrative that begins the story with Iranian retaliation rather than the escalation that preceded it”.

- Former Foreign Secretary Kanwal Sibal said India should have issued a statement condoling the death of Ayatollah Khamenei “to recognise that the head of state contrary to norms of international law has been politically assassinated”.

- Speaking about the March 4 submarine torpedo attack that sank the IRIS Dena “very close to India shores”, former Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran said that India must assert itself in the face of U.S. actions. “Tactical subservience can easily result in strategic irrelevance,” he added.

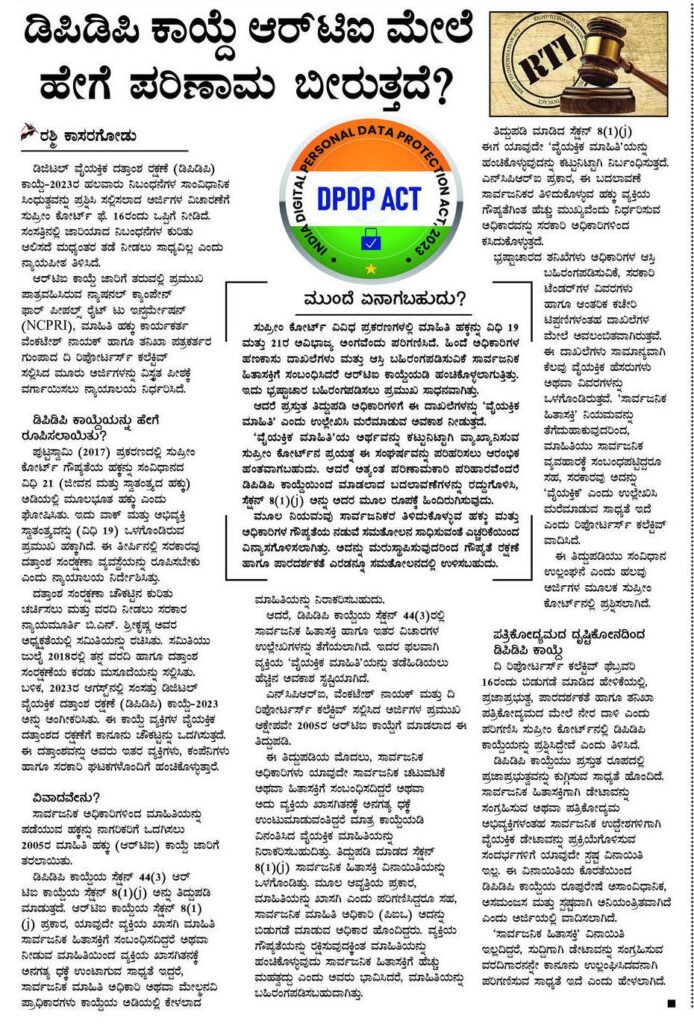

SC to study what constitutes ‘personal data’ in DPDP laws

Context: Chief Justice of India says a balance has to be struck between privacy and the right to information; court issues formal notice to Union government and asks advocate to frame questions of law.

- The Supreme Court agreed to examine what constitutes “personal data” under India’s new digital personal data law, which is being accused of using data privacy norms to block the right to information.

- A three-judge Bench headed by Chief Justice of India Surya Kant said the need to define “public data” and “personal data” has arisen following the implementation of the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023 and its corresponding Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025.

- The court issued formal notice to the Union government on a petition jointly filed by journalist Geeta Seshu and the Software Freedom Law Center, represented by senior advocate Indira Jaising and advocate Paras Nath Singh, who said the DPDP laws effectively stall journalists from accessing data of public interest concerning those who hold public offices.

- “The term ‘public interest’ has been deleted from the DPDP Act. Journalists cannot access data which is in public interest. A journalist need not have personal data, but needs information which is in the public interest to satisfy the public’s right to information and knowledge,” Ms. Jaising submitted.

- She said the Act does not clearly define terms such as “information” and “personal”. The state could mount sweeping surveillance on anyone, Ms. Jaising said.

- She highlighted how the Act allowed compensation for illegally accessing personal data to go directly to the government and not the injured person.

- “While the DPDP Act introduces a penalty-centric framework with fines running into hundreds of crores, such penalties are payable exclusively to the Consolidated Fund of India. The data principal whose privacy is violated receives no compensation, restitution or restoration, even in cases involving identity theft, financial fraud, reputational harm or dignitary injury,” the petition said.

- The Chief Justice said a balance had to be struck between privacy and the right to information. One right should not compromise the other, the court said.

- “At what point should data regarding a respectable person holding public office be treated as public and when should it be seen as personal,” the CJI asked. The Chief Justice pointed out that an individual’s data privacy has to be protected against sweeping provisions of law.

- “Entire personal data of the citizenry from a substantial part of the globe are flowing into bigwig private entities. Data has become the true wealth of the day,” Chief Justice Kant said.

- The court asked Ms. Jaising to frame questions of law and scheduled the case for detailed hearing on March 23.

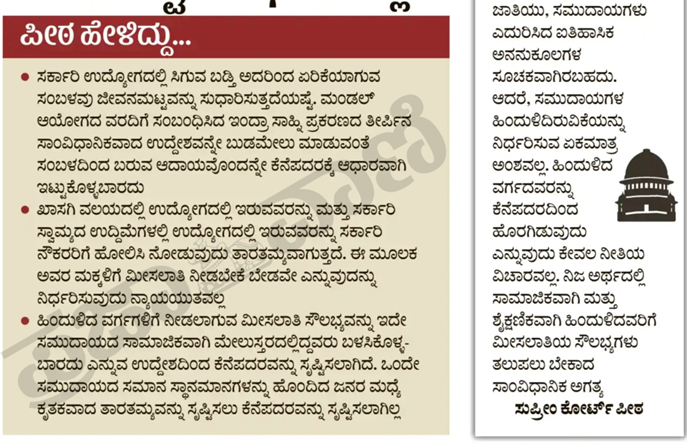

‘Parental income alone cannot set creamy layer status’

Context: Settling the decades-long confusion over how to calculate wealth or income to determine the creamy layer status of OBC candidates for reservation, the Supreme Court ruled this week that it “cannot be decided solely on the basis of the [parental] income”.

- This is likely to widen the reservation pool to include the children of senior public sector officials who had earlier been excluded on the basis of their parents’ annual salary income being above the ₹8 lakh threshold.

- The court said the framework to exclude the creamy layer from the OBC quota is clear that parental income from salaries and agricultural land are to be kept out while applying the income/wealth test.

- A Bench of Justices P.S. Narasimha and R. Mahadevan was hearing an appeal by the Union government against lower court rulings in favour of such OBC candidates. The cases arise from confusion over how to apply the income/wealth test for OBC children of PSU/PSB officials in the absence of equivalence with government posts, and whether income from salaries can be included in these calculations. During the hearings, OBC candidates selected in civil services examinations over the past decade argued that the Centre had incorrectly deemed them as part of the excluded creamy layer by including the salaries of their parents who worked in Central and State PSUs.

‘Based on status’

- In its March 11 judgment, the court noted that the creamy layer exclusion criteria were “status-based rather than purely income-based, reflecting the policy understanding that advancement within the governmental service hierarchy denotes social progression independent of fluctuating salary levels”.

- When the OBC quota was introduced in 1993, a guiding charter was created to exclude OBC candidates whose families had accumulated certain social and economic privileges over the years, known as the creamy layer.

- This would then allow reservation benefits only for those declared as “non-creamy layer” candidates, based on several criteria, including a crucial income or wealth test.

- The 1993 charter of the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT) had declared some OBC families ineligible on the basis of their occupations.

- Thus, children of people in constitutional posts, senior Central and State government employees, members of the armed forces, and property owners supposedly could not avail themselves of the OBC quota for the civil services.

- However, exceptions were carved out of these exclusions: for instance, children of MPs and MLAs; government officials who have been promoted, not hired, into senior positions; and owners of unirrigated agricultural land, among others, are all eligible for OBC quotas, subject to a parental annual income limit of ₹8 lakh.

- However, the DoPT has differentiated in how this income test is applied. With the help of a clarificatory letter issued in October 2004, the interpretation that has been applied was that parental salaries could be counted separately to apply the income test for determining the creamy layer for candidates whose parents worked in Central or State PSUs, an interpretation that was contested in the present cases.

‘Unequal treatment’

- Delivering the judgment in this batch of cases, the Supreme Court said, “Treating the children of those employed in PSUs or private employment, etc., as being excluded from the benefit of reservation only on the basis of their income derived from salaries, and without reference to their posts (whether Group A or B, or Group C or D) would certainly lead to hostile discrimination between parties who are similarly placed and would amount to equals being treated unequally.”

1. The Core Issue: “Creamy Layer” Determination

The central conflict arose because the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT) had been mechanically classifying candidates as “Creamy Layer” (and thus ineligible for reservation) solely based on the income of their parents, even if those parents were employed in PSUs, banks, or the private sector.

- The Court’s Ruling (March 11, 2026): A bench consisting of Justices P.S. Narasimha and R. Mahadevan ruled that a candidate’s status cannot be determined solely by parental income. The court emphasized that the “social and occupational status” of the parents must be the primary consideration, as stipulated in the 1993 and 2004 DoPT guidelines.

2. Historical Background of the “Creamy Layer” Concept

| Era/Event | Key Developments | Significance |

| 1979 (Mandal Commission) | Identified Socially and Educationally Backward Classes (SEBC). | Laid the foundation for reservation policies. |

| 1990 (V.P. Singh Govt) | Implemented 27% OBC reservation in central government jobs. | Formalized the reservation structure. |

| 1992 (Indira Sawhney Case) | SC upheld reservations but mandated the exclusion of the “Creamy Layer.” | Legal birth of the “Creamy Layer” concept. |

| 1993 (DoPT Memo) | Defined criteria for identifying the Creamy Layer. | Introduced social and occupational status criteria. |

| 2004 (DoPT Clarification) | Stated that salary and agricultural income should not be the sole basis for exclusion. | Used by the SC in 2026 to strike down mechanical income-based rejections. |

| 2026 (SC Judgment) | Ruled that occupation status is paramount; rejected income-only criteria. | Corrected administrative misuse of reservation guidelines. |

Paper-IV: General Studies 3

Committee on Responsible AI formed

Context: The Government of Karnataka has constituted a Committee on Responsible Artificial Intelligence (AI) to develop a comprehensive framework to guide the safe, ethical and transparent adoption of AI across government systems and public services.

- The committee, chaired by Kris Gopalakrishnan, co-founder of Infosys, and co-chaired by N. Manjula, Secretary, Department of Electronics, IT, Biotechnology and Science & Technology, brings together leading experts from industry, academia, policy and law.

- According to a government communique, the first meeting of the committee was held on Thursday (March 12, 2026) in Bengaluru, where members discussed the rapidly evolving AI landscape and the need to establish strong governance frameworks to ensure the responsible use of AI technologies, particularly in systems that impact citizens.

- The committee would develop a Responsible AI Policy and implementation road map for Karnataka, aimed at enabling innovation while ensuring that AI systems deployed across government are safe, fair, transparent and accountable, it said.

- Commenting on the initiative, Priyank Kharge, Minister for Electronics, IT, Biotechnology and Rural Development & Panchayat Raj, said, “As Karnataka enters its Deeptech Decade, the State is focused not only on accelerating AI innovation but also on ensuring that these technologies are deployed responsibly and in the public interest.’’

- The Responsible AI Committee brought together leading experts from industry, academia and policy to help shape a governance framework that promotes innovation while safeguarding transparency, accountability and citizen trust, said Mr. Kharge, adding, this initiative would help the State to continue to lead in building an AI ecosystem that is both cutting-edge and responsible.

AI for growth

- “Artificial Intelligence is a highly disruptive technology, and we are already seeing its potential to significantly accelerate the growth of Karnataka’s economy. If we are able to leverage this opportunity effectively, Karnataka can become the first in the country to develop a comprehensive framework for responsible AI—one that drives better citizen services, creates the jobs of the 21st century, and strengthens our innovation ecosystem,’’ said Mr. Gopalakrishnan, chairperson, Committee on Responsible Artificial Intelligence.

- By harnessing AI thoughtfully and responsibly, Karnataka would be able to significantly accelerate the growth of its economy, he further said.

- Some of the topics which came under discussion at the maiden meeting of the Responsible AI Committee included establishing responsible AI principles and policy guidelines for the State, aligned with India’s AI governance guidelines and global best practices, including legality, fairness, non-discrimination, privacy, safety, security, transparency, accountability, human oversight, inclusion and national interest.

Bengaluru woman becomes life-saving stem cell donor for teenager with severe aplastic anaemia

Context: A young aplastic anaemia survivor, who received a second chance at life through a life-saving blood stem cell transplant, met his donor in Bengaluru.

- Nineteen-year-old Anandu received the blood stem cells from 32-year-old Swathi, a resident of Bengaluru, after being diagnosed with severe aplastic anaemia – a life-threatening blood disorder.

Life-saving decision

- At 15 years, when he was in 10th grade, Anandu was diagnosed with the illness. Aplastic anaemia is a life-threatening condition in which the bone marrow fails to produce enough new blood cells. Physician V.P. Krishnan, consultant, pediatric hemato-oncology and BMT, MVR Cancer Centre and Research Institute, Kozhikode, advised that he undergo a stem cell transplant as it was the only curative option.

- Swathi, an IT consultant, had participated in a donor recruitment drive at her workplace in 2016, organised by DKMS Foundation, a non-profit organisation dedicated to fight against blood cancer and other blood disorders.

- In 2022, she received a call from DKMS requesting that she donate her stem cells, to which she agreed. Anandu had received support through the DKMS Patient Funding Programme, India, which provides partial financial assistance to eligible patients undergoing blood stem cell transplantation.

More donors crucial

- Reflecting on Anandu’s journey, Dr. Krishnan said, “He underwent a matched unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplant in early 2023. Although he experienced expected complications such as febrile neutropenia and mucositis during the transplant period, his recovery progressed well.”

- Today, Anandu is leading a healthy life and is preparing for his 12th board examinations.

- “Anandu and Swathi’s story highlights why more people need to register as potential blood stem cell donors. It is the generosity of donors like Swathi that makes life-saving transplants possible. With only 0.09% of India’s eligible population currently registered as donors, the chances of finding a match remain limited,” said Patrick Paul, executive chairman, DKMS, India.

- He also added that in Karnataka, more than 49,000 individuals have registered as potential blood stem cell donors with the DKMS Foundation India. Bengaluru alone accounts for approximately 38,000 registered donors.

- Individuals between 18 and 55 years of age, in good general health, with a BMI under 40, and not already registered are eligible to sign up as potential blood stem cell donors.

Paper-V: General Studies 4

Ethics Case Study: The Conflict of Public Health vs. Administrative Revenue Targets

1. Case Overview

The Karnataka government is currently managing two critical sectors—Excise and Dairy—where the pursuit of financial targets and operational efficiency is clashing with public health and safety. While the government aims for an excise collection target of ₹45,000 crore, it is simultaneously battling widespread liquor smuggling. Concurrently, the dairy sector reports that 3,049 milk samples were found to be adulterated, yet no criminal cases have been filed against the offenders.

2. Facts of the Case

Excise & Liquor Smuggling:

Target: ₹45,000 crore revenue; ₹32,492 crore collected as of February 2026.

Enforcement: 1,489 illegal liquor smuggling cases recorded in three years, primarily from Goa, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh.

Border districts like Belagavi, Raichur, and Kalaburagi are the most affected zones.

Milk Adulteration:

Scale: 3,049 samples adulterated out of over 1.5 million tested.

Hotspots: Hassan (788 samples), Ballari (588), and Shivamogga (434).

Administrative Response: Despite the presence of harmful substances like salt and sugar, no criminal cases have been filed; offenders receive only counseling and warnings.

3. Ethical Dilemmas

Revenue vs. Responsibility: Does the state’s focus on hitting high revenue targets in the liquor sector undermine the urgency of curbing illegal consumption and smuggling?

Deterrence vs. Counseling (The Milk Adulteration Issue): Is “counseling” an adequate ethical response to the contamination of a staple food consumed by children and the elderly, or does it reflect a lack of accountability?

Institutional Integrity: When enforcement is lax (as seen in the lack of criminal cases for food adulteration), does the state lose its moral authority to regulate the public?

4. Stakeholders and Values

Government: Responsible for fiscal stability (revenue) and ensuring Article 47 (improving public health) of the Constitution.

Public: Consumers rely on the state to ensure the safety of food and the regulation of intoxicating substances.

Enforcement Agencies (Excise/Food Safety): Expected to balance strict law enforcement with administrative efficiency.

5. Options for Action (The Policy/Ethics Committee View)

If I were a member of a high-level committee reviewing these issues, I would propose the following multi-dimensional strategy:

A. For Excise Policy (Liquor Smuggling)

Move beyond “Revenue-only” KPIs: Transition from purely monetary targets to “enforcement-quality” targets. Performance should be measured by the reduction in illegal smuggling incidents, not just tax collected.

Technological Integration: Implement E2E (End-to-End) tracking using QR codes on liquor bottles to eliminate leakage and ensure taxation is based on ABV (Alcohol By Volume) as proposed, which is a scientifically more ethical way to tax.

Inter-State Cooperation: Establish joint task forces with border states to choke the supply chain of illicit liquor.

B. For Food Safety (Milk Adulteration)

Zero Tolerance Policy: Shift from a “counseling-only” approach to a “graded penalty” system. First offenses could involve heavy fines, and repeat offenses must result in criminal prosecution and license cancellation.

Transparency & Disclosure: Publicly name the primary cooperatives or private dairies where repeated adulteration is detected to ensure consumer trust is backed by transparency.

Strengthen Legal Framework: Ensure that food safety laws are applied consistently, regardless of whether the supplier is a primary cooperative or a large private firm.

Ethics Case Study: The Conflict of Public Health vs. Administrative Accountability

1. Case Overview

The state of Karnataka is currently facing a dual crisis in essential supply chains: the systemic adulteration of milk (a staple food) and the severe chemical contamination of vegetables supplied to Bengaluru. While the government is pursuing revenue targets in sectors like excise, these reports highlight a breakdown in regulatory oversight, where economic interests and “administrative convenience” appear to be taking precedence over the fundamental right to safe food and public health.

2. Key Facts

Milk Adulteration: 3,049 samples were found adulterated with salt, sugar, and other substances. Despite the legal provision for criminal prosecution (up to life imprisonment), no cases have been filed. Offenders are merely “counseled.”

Vegetable Contamination: A CPCB report indicates severe contamination of vegetables with lead, pesticides, and heavy metals. Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) are reportedly non-functional, and there is a significant gap between existing sewage treatment capacity (1,200 MLD) and the required capacity (1,800 MLD).

Excise Policy & Smuggling: High revenue targets (₹45,000 crore) for excise have been linked to systemic challenges in controlling illegal liquor smuggling across borders (Goa, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh).

3. Ethical Dilemmas

Revenue vs. Life (The Excise Dilemma): Is it ethical for the state to set aggressive revenue targets that may lead to the neglect of enforcement, thereby allowing illegal trade to flourish?

The “Counseling” Trap (The Accountability Dilemma): In cases of food adulteration (milk), choosing to “counsel” offenders instead of filing criminal charges is a failure of deterrence. It prioritizes the comfort of the supplier over the health of the consumer.

Negligence vs. Rights (The Environmental Dilemma): The contamination of vegetables through untreated sewage is a violation of the citizens’ right to health. The state’s failure to maintain STPs indicates a breach of the social contract.

4. Stakeholders and Values

The State/Government: Bound by Article 47 of the Constitution to improve public health; however, it is currently struggling to balance this with fiscal revenue goals.

Public/Consumers: Victims of silent health crises (e.g., fatty liver, nervous system issues mentioned in the vegetable report). They hold a legitimate expectation of safety.

Regulatory/Enforcement Agencies: Expected to exercise impartial and stringent oversight, which is currently being undermined by a preference for “soft” enforcement.

5. Proposed Governance Framework (Ethical Solutions)

As a member of an ethics review committee, I propose the following shifts:

A. Shift from “Counseling” to “Compliance”

Zero-Tolerance Prosecution: Food safety is non-negotiable. Any detected adulteration must trigger an automated legal process. “Counseling” is appropriate for educational settings, not for criminal food adulteration.

Public Audits: Create a public digital dashboard that names cooperatives and dairies that have failed quality tests, ensuring market-driven accountability.

B. Aligning Revenue with Public Good

Earmarked “Health Cess”: A portion of the revenue collected from excise and other high-growth sectors should be legally ring-fenced for public health infrastructure, such as modernizing STPs and water treatment.

Performance-Based Enforcement: The performance metrics for officials should include “reduction in contamination cases” rather than just “tax collected.”

C. Inter-Departmental Accountability

Integrated Monitoring: Since the vegetable crisis involves Irrigation, Agriculture, and Urban Development, the proposed inter-departmental committee must have a time-bound mandate with personal liability for officials if water quality standards are not met.

Source: The Hindu